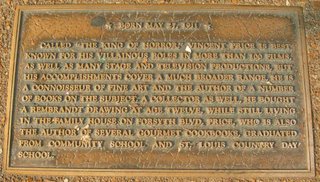

Vincent Price: A Patron's Patron

Everytime I do research on Price, I'm overwhelmed with significant details from his life with art. His loving daughter has written a biography, and I'm almost tempted to do one myself.

Everytime I do research on Price, I'm overwhelmed with significant details from his life with art. His loving daughter has written a biography, and I'm almost tempted to do one myself.Perhaps the best source of Price on art is a lengthy interview with him conducted a year before his death. The Smithsonian Archives of American Art, a visionary institution of which Price was a founding member, recorded the oral history of the beginnings of its existence and Price's impact on the appreciation of fine visual arts in the U.S.

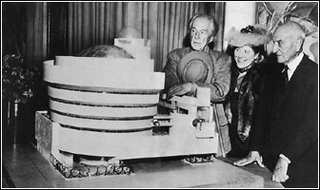

Educated at Yale University in art history, Price spent a number of years touring America, giving talks to regular people on the subject of art to encourage interest. Moving to LA with his showbiz career he opened a commercial art gallery and encouraged the founding of a modern art institute in a town almost barren of high culture. Price worked with Sears to sell some 50, 000 original works of art (many commissioned by him) Here's a quote from the Wall Street Journal:

"In 1962 Price was approached by George Struthers, Sears's vice president of merchandising, who believed his company could sell fine art to the American public the same way it sold lawn mowers and ladies' underwear. Price agreed to pick the pieces and serve as spokesman, and the Vincent Price Collection of Fine Art was off and running, first in Sears's Denver store, then in other stores across the country, with a mail-order line added the following year. Not surprisingly, much fun was poked at the idea of Sears going into the fine-art business. The New Yorker even ran a cartoon about it ("It's not generally known, but we picked up this little Rembrandt etching at Sears, Roebuck"). But the company had the last laugh: During Sears's nine years in the art trade, it sold some 50,000 works at prices ranging from $30 to $3,000, many of them bought on installment plans that made it possible to purchase certain works for as little as $5 down and $5 a month. The prices were affordable, too, with Picasso's lithograph "Frederic Joliet Curie" going for $300, the equivalent of $1,850 in today's dollars--just about what the same print costs now."

"In 1962 Price was approached by George Struthers, Sears's vice president of merchandising, who believed his company could sell fine art to the American public the same way it sold lawn mowers and ladies' underwear. Price agreed to pick the pieces and serve as spokesman, and the Vincent Price Collection of Fine Art was off and running, first in Sears's Denver store, then in other stores across the country, with a mail-order line added the following year. Not surprisingly, much fun was poked at the idea of Sears going into the fine-art business. The New Yorker even ran a cartoon about it ("It's not generally known, but we picked up this little Rembrandt etching at Sears, Roebuck"). But the company had the last laugh: During Sears's nine years in the art trade, it sold some 50,000 works at prices ranging from $30 to $3,000, many of them bought on installment plans that made it possible to purchase certain works for as little as $5 down and $5 a month. The prices were affordable, too, with Picasso's lithograph "Frederic Joliet Curie" going for $300, the equivalent of $1,850 in today's dollars--just about what the same print costs now."Price reasoned:

"I felt that here at last was a chance to expose the U.S. public to fine art at reasonable prices," Price explained. "The average housewife doesn't realize that she can buy an original work of art for very little money." Critics may have winced at the effusive catalog copy ("A Picasso can turn your dull den into a spicy fiesta!"), but there was nothing unserious about the works themselves, all of which were originals or limited-edition multiples, not cheap reproductions."During the AAA interview, Price discussed his friendship with and the importance of David Hockney to developing the art community in LA:

"What David has done in this community—and for this community, and with this community, and by this community—has been what the other people didn’t do. What we were talking about. Huxley did not come and found a little group of people around himself. Neither did [von] Sternberg, or Schönberg, or any of them. But David has. David is as well-known in this town as if he had been born [here—Ed.]. And he loves it, he adores [it]. And when he came here. . . . I knew him in England quite well and saw his first show. David has done what these other people didn’t do: He’s made a community around himself, with. . . . I’m just trying to think of some of the people that he knew first here."

Vincent spoke about his community development work in East Los Angeles:

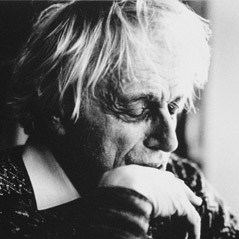

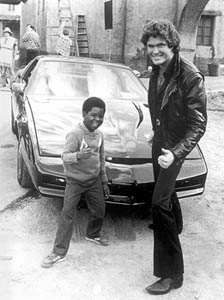

Vincent spoke about his community development work in East Los Angeles:My interest in East Los Angeles stems from a lot of, for different reasons that are all good. One of them very definitely was that a lot of the sort of bitterness that you must feel that I felt about that period that we’ve been talking about, the people who let us down, the people who didn’t show interest, the people like Arensberg, who was going to take his collection somewhere else anyway. My involvement with East Los Angeles is because it couldn’t happen there. It’s much too honest a neighborhood. It is completely isolated from this world over here. It’s completely different. I was invited to come and talk to this college, which was about five quonset huts on a mudflat, by a woman named Judith Miller. And she wanted me to talk about the aesthetic responsibility of the citizen. That’s a pretty classy title. Well, it fascinated me since the aesthetic responsibility of three quonset huts on a mudflat was not very high. But I went, and I fell in love with it, fell in love with the whole Latino community—Chicano, whatever they call it now. But this was where I decided to put my energy, and to do it without any way identifying myself with it. Because I was accused here of using the arts as an entrée to a world that I didn’t want to be in anyway. People sort of said, “He’s an art snob,” and I just didn’t want to be an. . . . It’s very difficult for me to talk about it. But that’s why forty-five years ago I started this collection in East Los Angeles. It’s been used, it’s grown, it’s produced some very exciting artists. It’s produced [Edward James] Olmos, you know, that wonderful actor, who credits the gallery with part of his life. ('Vincent Price', charcol drawing by Rico LeBrun, 1950)And there's much, much more. The interview's the place to go. The Archives of American Art is an awesome reference. The oral history interviews are the best. (photo: Mick Cusimano)

In the absence of general interest, it's the serious, commited individuals, like Vincent Price, who lead others to nurture and grow a vital fine arts culture.